The fact that this article was on Wired makes me wonder if they programmed a highly sophisticated robot write it. ¿Can we have a flip-side to the Turing Test? — the test to see if a work is so dumb you can’t e’en tell if ’twas written by a human or a robot.

It starts out fair-’nough, albeit with questionable assertions:

Literature is language-based and national; contemporary society is globalizing and polyglot.

Somebody’s ne’er heard o’ translation.

Society has always been polyglot — hence why translation has existed for centuries. E’en in Shakespeare’s time English would be mixed with French, Latin, & e’en Greece ’cause o’ how big an impact those cultures had on English culture.

Vernacular means of everyday communication — cellphones, social networks, streaming video — are moving into areas where printed text cannot follow.

Solution: don’t print the text.

¿How is this a problem for literature? ¿Why does literature need to be printed? ¿’Cause printing feels good?

Literature is quite great @ moving into cell phones, social networks, & e’en streaming videos. In fact, social networks are primary build up o’ literature, & half o’ most streaming videos involves textual chat. E’en as video builds up popularity online, text is still supreme. In fact, society’s probably mo’ literate now than it’s e’er been thanks to text’s supremacy o’er the web. Maybe in the past we could worry ’bout some dystopian future wherein everyone’s a mindless slave in front o’ the flashing colors o’ their screen, blissfully free from reading a single word; but nowadays, while the dystopian future o’ people being mindless slaves in front o’ technology may still be a prospect, you can bet it’d involve reading reams o’ text.

Intellectual property systems failing.

This implies an economic barrier to literature’s success; but the literature industry seems to be quite adept @ making tons o’ money on literature, e’en if it’s mostly shallow companies that make the money. & technology such as eBooks & Kindles have, if anything, improved the profitability o’ literature.

No, in a world where the leading country in art production still keeps works copyrighted 90 years after its creator’s death, & wherein international laws like TPP threaten to push stronger laws on the rest o’ the world, copyright is still ’live & well, despite the existence o’ a few mo’ online pirates.

If anything, literature is hindered mo’ by the increasing attention given to profitability o’er quality, leading to lowering standards o’ literature.

Means of book promotion, distribution and retail destabilized.

Which is always terrible in markets.

So now rather than authors relying on busy big businesses to market their work, they have social media, where they can do it themselves mo’ effectively. I think by “destabilized”, you mean “made easier & mo’ effective”.

Ink-on-paper manufacturing is an outmoded, toxic industry with steeply rising costs.

Which is why it’s a good idea it’s becoming less prevalent.

¿How is this a challenge? ¿Would it kill these writers to just once not contradict their own core theses?

Core demographic for printed media is aging faster than the general population.

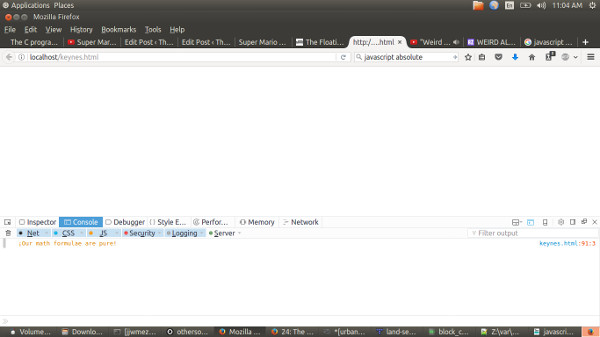

( Laughs ). No, that’s physically impossible. Nobody can “age” faster than anyone else. Aging is simple existing in time. ’Less print readers have time traveling devices to make them go forward in time mo’ quickly, I don’t think so — & I find the prospect that the least technologically sophisticated people would have technology centuries beyond what’s possible now to absurd to chew.

I think you meant the less weaselly words ( though still fragmentary ), “Core demographic for printed media is dying off mo’ ” That’s mo’ depressing to consider, but mo’ accurate.

Maybe 1 o’ these “challenges” should’ve been the devolving quality o’ diction as online writing succumbs mo’ & mo’ to sterile & vague businessese.

Failure of print and newspapers is disenfranching young apprentice writers.

No, that’s just Republicans.

So… ¿The failure o’ print is affecting those who use it the least the most? I’d think it’d be the oldest people who are still unable to use popular technology competently that’d be most blocked from success in the industry. Young people familiar with new technology should feel in bed with… well, new technology.

¿Or is he trying to claim that literature cannot continue without print & newspapers & that young “apprentice” writers are becoming less literate? I’ve already ’splained why that’s obviously false.

Media conglomerates have poor business model; economically rationalized “culture industry” is actively hostile to vital aspects of humane culture.

& now we degenerate further into meaningless buzzwords.

¿What the fuck is “economically rationalized ‘culture industry’”?

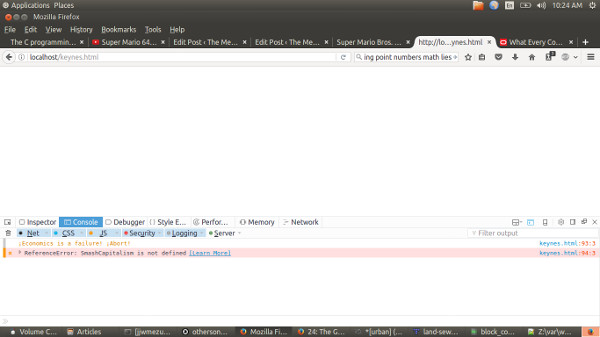

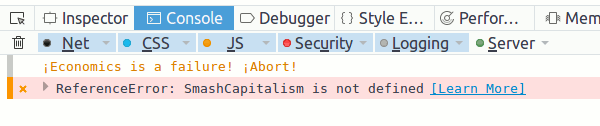

I certainly don’t think conglomerates being actively hostile to vital aspects o’ humane culture is anything contemporary. We’ve been calling that kind o’ thing “capitalism” for the past 2 centuries, & it’s probably 1 o’ the only things certain in this world, other than maybe death & tax loopholes.

Long tail balkanizes audiences, disrupts means of canon-building and fragments literary reputation.

& now we’re delving into outright fantasy. I don’t know what creature “Long tail” is, but I do hope the Good Wizard Whitebread stops him with his Shape Spells before that foul beast can “balkanize” the audience with its 4th-wall-breaking powers.

¿Whose literary reputation is hurt? This writer couldn’t go the whole way o’ pretending there’s only 1 reputation that exists by giving that phrase an article, so we’re just going to have to figure it out ourselves.

Maybe this is an attempt to recreate the strengths o’ modernist literature through blog posts. You have to dig into deep analyses to understand what this loon’s trying to say, just like with James Joyce.

Digital public-domain transforms traditional literary heritage into a huge, cost-free, portable, searchable database, radically transforming the reader’s relationship to belle-lettres.

¿By making it mo’ accessible? Yes, nothing is a greater challenge to literature than the fact that mo’ people can indulge in it.

¿Remember when we used to fear that we’d lose literary classics — those ol’ dystopians like Fahrenheit 451? That’s ol’ news: now we worry ’bout too many people being able to get access to Shakespeare, apparently.

Contemporary literature not confronting issues of general urgency; dominant best-sellers are in former niche genres such as fantasies, romances and teen books.

I’m almost tempted to rewrite these quotes in all-caps to emphasize how much they sound like some hokey ol’ computer. “BEEP BOOP. COMTEMPORARY LITERATURE NOT CONFRONTING ISSUES OF GENERAL URGENCY. ERROR CODE 728”.

Yes, ’cause no fantasy, romance, or teen book could e’er confront modern problems. I could see the assumption for the 1st for someone immensely ignorant & shallow ( A Song of Ice and Fire could tell you a lot mo’ ’bout the complexities & corruptions o’ political forces that is just as applicable to modern society as medieval than some lit fic that dicks round with word structure & takes place entirely within a literary professors head ); ¿but romance & teen books are irrelevant to contemporary problems?

Considering the author ne’er bothers to specify what he considers to be “issues of general urgency”, we’re left with yet ’nother blanket assertion that has li’l backing, & is probably mo’ wrong than right.

Here’s ’nother better problem for modern literature: “Dumbs down complex issues into simplistic listicles”. If only there was a way to write anything with any semblance o’ depth online. But that’s impossible, ’course. I mean, you can put the entirety o’ Structure and Interpretation of Computer Programs online; but you can’t write anything that intelligent online. Those are the rules.

Barriers to publication entry have crashed, enabling huge torrent of subliterary and/or nonliterary textual expression.

Just like this 1.

Algorithms and social media replacing work of editors and publishing houses; network socially-generated texts replacing individually-authored texts.

’Cause collaboration has ne’er created anything valuable, artistically. Nor can anyone hope to do anything individualistic online. Contrast this with, say, Shakespeare, who ne’er worked with anyone else & ne’er had anything to do with the cultural currents o’ his time. He was just some isolated crab in a cave, writing everything from his pure invention, with no inspiration from anyone else @ all. That’s how true writers write. Or how ’bout T.S. Eliot, who filled his poetry with references to ancient literature that everyone in his literary club knew — what we might call “literary memes” today.

As for algorithms & social media replacing the work o’ editors & publishers, that’s false — not the least o’ which ’cause algorithms & social media don’t have any self-consciousness to make decisions independent o’ their fleshy masters. A mo’ accurate statement would be that all 4 o’ these things are guided by profit, which has been the guide to the literature industry since… well, ’twas an industry. As it turns out, industries are always guided by profit, ’cause if it’s not selling for the purpose o’ making money, it’s not called an industry. ’Gain, this is called “capitalism” & has existed for centuries.

If he were making the point that profitability & quality are diverging, that’d be a coherent argument; but he ne’er comes close to proving it. If this writer were half as knowledgable o’ the history o’ literature as he pretends to be, he’d know that the literature industry has been glutted with profitable but low-quality crap fore’er. ¿Know how I always liked to call shitty online writing Boon & Mills 2.0? Yeah, there’s a reason: it’s to emphasize that this is a modern version o’ an ol’ form o’ pumping out cheap, mindless literature. The corollary is that there was a traditional means that existed since the early 1900s. This writer might be pleased to know that back in the 1930s Hemingway, too, bitched ’bout the proliferation o’ cheap romance literature — ’cept he didn’t blame new technology so much as those bitchy womenfolk. As it turns out, the idea that investing a lot o’ money in truly intelligent writing is less profitable than investing less money in convincing lots o’ people that crap is gold was conceived by companies centuries ago.

“Convergence culture” obliterating former distinctions between media; books becoming one minor aspect of huge tweet/ blog/ comics/ games / soundtrack/ television / cinema / ancillary-merchandise pro-fan franchises.

1. I won’t e’en pretend to understand what “ancillary-merchandise pro-fan franchises” means. Well, I do know: it means nothing. It’s just something the writer thought sounded cool. I would imagine that any franchise would be “pro-fan”; Shakespeare certainly didn’t write his works with the intent that people would hate them. I’m also not sure if it’s s’posed to be the literature that’s ancillary or the merchandise. In context, it seems as if it should be the literature, since I can’t imagine someone complaining ’bout the problem o’ literature being that they don’t care ’nough ’bout selling Mr. Darcy action figures; however, its connection to “merchandise” with a hyphen seems to state that it’s the merchandise that’s ancillary. The meaning o’ what he actually wrote directly contradicts what makes sense in context — which is no rarity, e’en in this short post.

2. How dare you mix your filthy lesser media in my literature. Classic literature sure ne’er mixed with other mediums. Ne’er mind that Shakespeare’s plays were “ancillary” to literature & were made primarily to be performed in essentially an older version o’ television; that didn’t apparently hurt its stature as the highest point o’ English literature. Meanwhile, that hack James Joyce would love to mix in songs, advertisements, & e’en camera techniques from early cinema into that dumb piece o’ pop-culture pollution known as Ulysses.

3. People who can’t e’en bother to use “/”s consistently shouldn’t be judging others on their literacy.

Unstable computer and cellphone interfaces becoming world’s primary means of cultural access. Compositor systems remake media in their own hybrid creole image.

Let’s ignore the fact that his denigrating comparison o’ different window sizes changing literature to creoles is racist & hilariously worded in the most pretentious way possible & ’stead focus the fact that he seems to think literature falls apart if put in a different-sized rectangle. This is in contrast to books, which have always had the same standard size for all published books fore’er.

I’m actually not e’en sure I interpreted his incredibly vague diction correctly. I’m not sure what part o’ computer & cellphone interfaces are “unstable”, since an “interface” is just any way you use them, which is a large problem domain.

Also, love the redundancy: he could’ve just said that “computers are becoming world’s primary means of cultural access”, since cellphones are, by definition, computers & interfaces are, by definition, the way you access computers. Nothing’s mo’ literate than using mo’ words just for the sake o’ mo’ words. That’s what Strunk & White always said, a’least.

As for “Compositor systems”, they are just the programming techniques operating systems use to keep screens from flickering & give windows spiffy affects when they’re minimized, as well as the way image blending works in Photoshop. Not sure how any o’ that “remake[s] media in their own hybrid creole image”; the latter doesn’t e’en seem to have anything to do with literature @ all. ¿Is he trying to imply that programmers try to hide subliminal messages in the screen’s double buffer?

Scholars steeped within the disciplines becoming cross-linked jack-of-all-trades virtual intelligentsia.

With the context o’ this writer / robot’s stuffy language, I can’t imagine him saying “the disciplines” or “jack-of-all-trades” without quotation marks. “These scholars — always be steepin’ in those disciplines, ¿you know what I’m saying?”

This 1’s actually coherent, but not relevant to literature. Also, he doesn’t provide any evidence that it’s true or e’en a bad thing. He basically just asserts something ’gain with the stupidest o’ diction & leaves us, as if his profound li’l fortune cookie o’ wisdom were ’nough.

Academic education system suffering severe bubble-inflation.

Wired listicle plagiarizing The Economist headline.

I had to rewrite that sentence to make it closer to the terribleness o’ the original, since my natural proclivity gainst English atrocities made me neglect the participle. I in my silliness wrote “plagiarizes” in simple present tense, which is far too concise to be good.

¿How the fuck can an education system have inflation? I guess this writer is trying to say that there’s too many colleges & not ’nough demand, said in an inane mixed metaphor with currency & economic bubbles ( ¿Why both? ’Cause the writer had to fill what was still a much shorter word requirement than e’en this post I’m writing & couldn’t fill that word demand with substance ). With how expensive colleges have gotten, I doubt that.

Polarizing civil cold war is harmful to intellectual honesty.

( Pause for laughter ).

All right: this is the line that inspired me to do this whole post. This deserves to be enshrined. Forget those wimps who read Eye of Argon without laughing; I’d like to see them read this sentence with a straight face.

1. ¿A polarizing war? ¡You don’t say! That’s right up there with “wet water” or “crappy shit”.

2. ¿Is the “civil cold war” some fantasy hybrid he’s writing ’bout in some novel he’s writing? ¿Do those evil commie Soviets develop a time machine & conspire to use it to go back & force the north to lose the civil war in hopes o’ debilitating the US’s global power, allowing the Soviet Union to be dominant? ’Cause you’d probably do much mo’ for contemporary literature by writing that amazing plot than writing this dumb listicle.

3. Sentence fragment is harmful to Hulk brain.

4. After making all these jokes, I’ve realized that I still have no idea what this crackpot is talking ’bout. Stop trolling: everyone knows it’s the Worldwide Mad Deadly Communist Gangster Computer God™ that controls everything, not some dumb civil cold war. Leave the insane ramblings to the experts, please.

The Gothic fate of poor slain Poetry is the specter at this dwindling feast.

Looks like you failed to copy that headline from World News Weekly & still had that line from that emo poetry you were composing in your clipboard. Oops.

I’ll give this article 1 thing: usually I feel a bit soul-sick reading these listicles, just rolling my eyes & thinking, Not this vapid shit ’gain. This article was a’least refreshingly creative in its insanity, making me slap my forehead & think, ¿What the fuck? ¿Where’d you e’en come up with that garbled mess o’ words? I’m still not sure that these lines didn’t all just come from the Chomskybot.